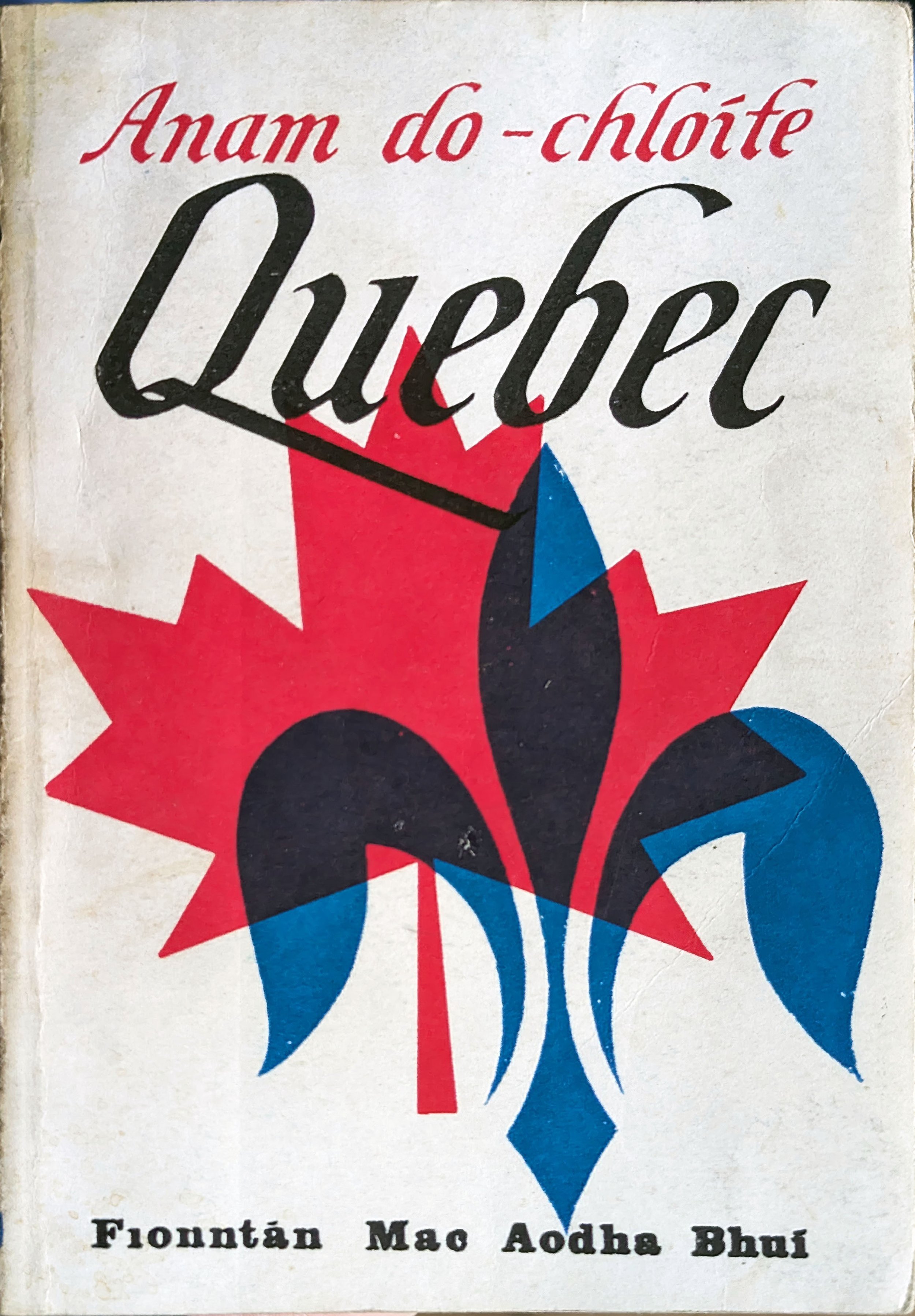

Anam Do-chloíte Québec (1968)

Fionntán mac Aodha Bhuí, Muileann gCearr, Co. na hIarmhí

Fionntán mac Aodha Bhuí was not only a highly accomplished architect but also a talented writer. Born in an Muileann gCearr, Co. Westmeath, in 1924, his journey into the heart of Québec's cultural identity began during an extensive visit to Canada and the United States in 1962, where he was captivated by the unique challenges and resilience of Québec and its people.

This initial fascination with Québec's cultural and linguistic dynamics evolved into a lifelong interest for Fionntán. In 1968, he published a significant work titled "Anam Do-chloíte Québec" (The Indomitable Soul of Québec). Within the pages of this book, he delved into the historical narrative of Québec within the broader context of Canada, spanning from 1604 to his contemporary era. Through meticulous research and thoughtful analysis, Fionntán sought to unravel the complex threads of Québec's cultural identity, shedding light on the struggles and triumphs of its people. Fionntán's contributions remind us of the power of literature and research in promoting cross-cultural dialogue and fostering a more inclusive world.

Fionntán mac Aodh Bhuí passed away in Co. Roscommon in 2012.

“Dar le Durham nach raibh le déanamh ach oideachas Gallda a thabhairt do na páistí Francacha agus bheidís ina “happy English children” gan aon ró-mhoill. Ach dá thuisceanaí é, níor thuig seisean méid ghrá phobail Québec dá ndúchas.

Chaill Durham a phost sa deireadh toisc é a bheith ró-bhog (dar le Loyalists Ontario) leis na daoine a ghlac páirt in éirí amach 1837. D’imigh sé abhaile go Sasana, áit a bhfuair sé bás den eitinn i mí Iúil, 1840.

Cuireadh Québec agus Ontario le chéile faoi aon Rialtas amháin, mar a bhí molta ag Lord Durham, ach má chuir, bhí Québec go nimhneach ina éadan an aontaithe chéanna. Ní hé amháin go mbeadh fiacha Ontario mar chúram orthu feasta ach lena chois sin, rud níos measa, bheadh na Béarlóirí chomh láidir anois le Franciseoirí sa Pharlaimint ainneoin sliocht na bhFrancach a bheith níos líonmhaire go fóill i gCeanada. Ceapadh Kingston (Fort Frontenac na seanaimsire) mar ionad parlaiminte, rud eile a chuir míshásamh ar phobal Québec, mar ba cheantar Béarla é faoi seo. Chuaigh an taobh eile le báine nuair a toghadh Frainciseoir, La Fontaine, ina phríomh-aire cúpla bliain ina dhiaidh sin, agus bhí cúrsaí chomh holc sin gur bhris ar shláinte an Ghobharnóra, Sir Charles Bagot, agus go bhfuair sé bás dá dheasca i mí Bealtaine, 1843.”

“According to Durham [Governor General of British North America] the only thing that had to be done was to give English education to the French children and they would be “happy English children” without any delay. But if he was an understanding man he certainly didn’t understand the amount of love that the people of Québec have for their heritage.

Durham lost his job in the end because he was too soft (according to the Loyalists of Ontario) on the people who had taken part in the rebellion of 1837. He went home to England, the place he died of tuberculosis in July 1840.

Québec and Ontario were put together under a single Government, as Lord Durham had recommended, but if they were so put Québec was vehemently against that same union. Not only that the debts of Ontario would be henceforth be put onto them but along with that, something much worse, the English-speakers would be as strong now as the French-speakers in the Parliament despite the descendants of the French still being more numerous in Canada. Kingston (previously Fort Frontenac) was decided as the place of parliament, another thing that made the people of Québec unhappy, as it was an English-speaking city at the time. The other side was aghast when a Frensh-speaker, La Fontaine, was elected as Prime Minister a few years after that, and things were so awful then that the health of the Governor, Sir Charles Bagot, broke and he died due to it in May 1843.”

“An rud atá cinnte ná go bhfuil an t-am thart go deo go mbeidh Frainciseoir Ceanadach sásta bheith mar shaoránach den dara grád ina thír féin. Tá an óige go mór-mhór tinn tuirseach den scéal. “Is í Québec mo bhaile,” arsa fear óg le Hugh McLennan le déanaí, “agus teastaíonn uaim mo bheatha a chaitheamh anseo i bhFraincis, agus ní i mBéarla, ón a naoi go dtí a cúig i mo phost.”

…Ceapadh Éireannach, ag machnamh dó ar fhulaing a náisiúin féin de ghéarleanúint nach ró-léanmhar ar fad í an stair a bhí ag Québec ó cuireadh faoi chois í. Agus gan amhras ní raibh aon Chromail nó Drochshaol aici mar a bhí ag Éirinn. Ina dhiaidh sin, ní féidir linn ach meas a bheith againn ar chine chomh beag - ní raibh inti ach 60,000 de phobal nuair a thréig an Fhrainc í dhá chéad bhliain ó shin - mar gheall ar a bhfuil déanta aici. Fágadh mar dílleachtaithe iad, scata beag i gcúinne de Mheiriceá Angla-Sacsanach, agus mhair siad mar chine faoi leith, go dtí an lá inniu féin. Mhair siad nuair ab éasca ar fad dul le sruth agus géilleadh, thugadar a n-oidhreacht slán isteach sa fichiú aois trí dheonú Dé agus a mian domharfa féin.”

“The thing that is certain is that the time is entirely past that a Fench-speaking Canadian will be satisfied to be a second-class citizen in his own country. The youth are very much sick and tired of the story. “Québec is my home,” said a young man to Hugh McLennan lately, “and I want to live my life here in French, and not in English, from nine-to-five at my job.”

…An Irish person would think, reflecting on the suffering of his own nation due to persecution, that it isn’t entirely too grevious the history of Québec since it was conquered. And without a doubt it had no Cromwell or Great Famine as Ireland had. Following that, we cannot have but respect for a population so small - there was not but 60,000 people in it when France abandoned it two hundred years ago - because of what they have done. They were left as orphans, a little group in a corner of Anglo-Saxon America, and they survived as a separate people, up until today. They survived when it would have been easier entirely to go with the flow and yield, they brought their inheritance wholesale into the twentieth century through the providence of God and their own unkillable will.”

Adapted from: Mac Aodha Bhuí, Fionntán. 1968. Anam Do-chloíte Québec. Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta: Baile Átha Cliath.