The Gagetown Gaels

Nestled amidst the verdant expanse of the Gagetown plateau, bordered by the majestic Wolastoq (Saint John River) on its northern and eastern fringes, lay a landscape teeming with stories of resilience, heritage, and loss. This fertile terrain has been inhabited by the Wolastoqiyik people since time immemorial. Following the expulsion of Acadian settlers in 1758, the Gagetown area bore witness to a transformative chapter in Canadian history with the arrival of United Empire Loyalists, fleeing the turmoil of the American War of Independence, in 1783.

As the 19th century unfolded, the Gagetown plateau burgeoned into a thriving hub of lumbering and farming, its character indelibly shaped by waves of immigrants from across the Atlantic. Among these settlers, it was the Irish who left an enduring mark, their origins from Tyrone, Fermanagh, and beyond reflected in the very names that dotted the landscape: Hibernia, Clones, Coote Hill, Enniskillen, and Summerhill.(1)

Amidst the bustling communities that sprang forth, a surprising facet of Irish heritage persisted: the presence of small Irish-speaking enclaves.(2) Contrary to prevailing beliefs, 80% of these speakers were Northern Irish Protestants, their vibrant Gaelic culture even celebrated by members of the local Orange Lodge.(3) As revealed by the Canadian census of 1901, the Gaelic subculture ran deep, with 22% of the population being native speakers of Irish. These speakers spanned generations, with only 2% having been born in Ireland and 30% being under the age of 20. The Gagetown Gaels explode the myths of who spoke Irish and how quickly they assimilated.

As Bradford Gaunce, census study co-author, noted: “The assumption that the language did not survive in the Diaspora is not based on hard evidence.”(4)

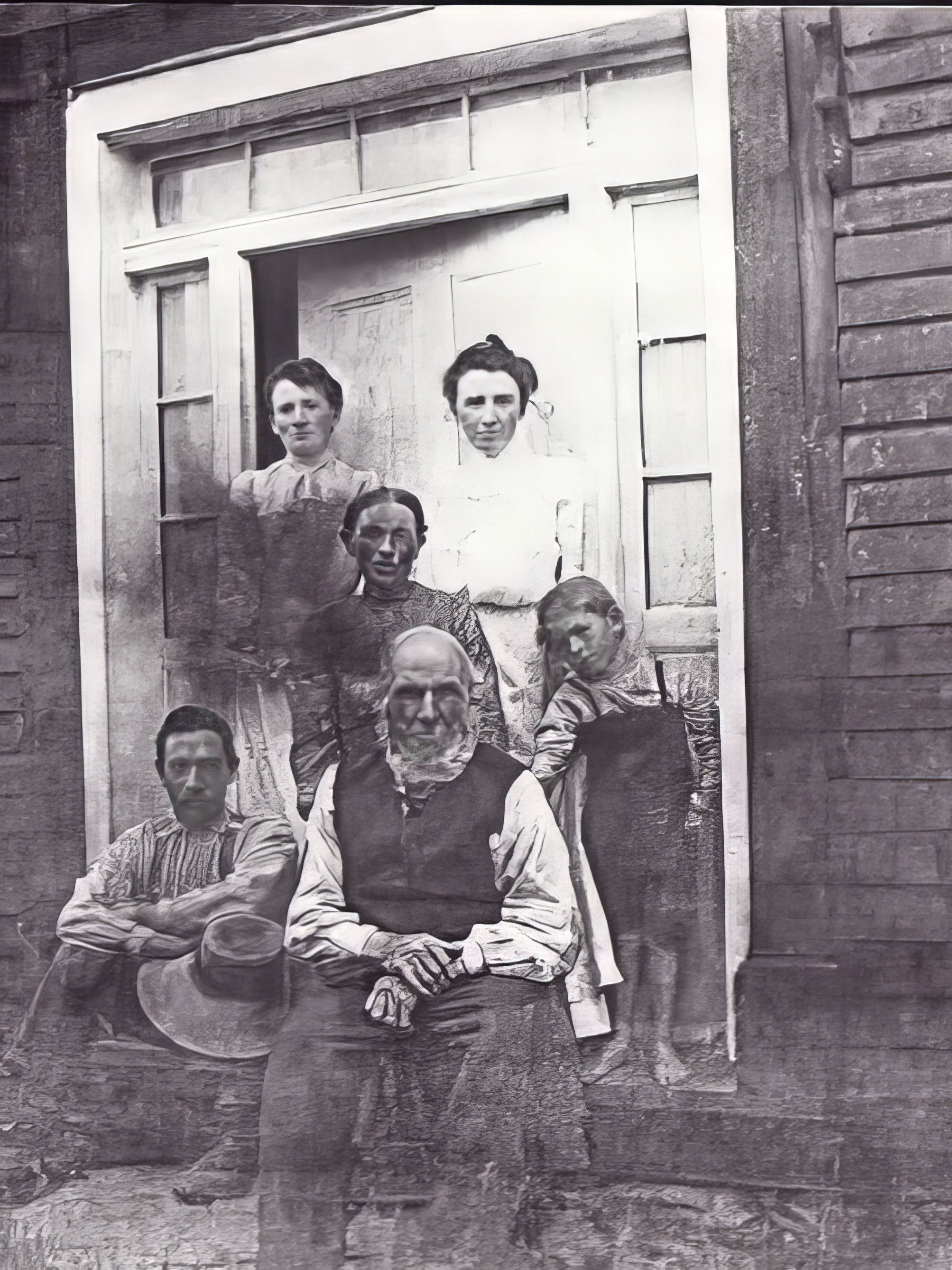

The Armstrongs

The Armstrongs, a family hailing from Summerhill, epitomized these Gagetown Gaels, embodying a heritage intertwined with the rhythms of Irish speech. John Armstrong, born into a Protestant, Irish-speaking family in Northern Ireland in 1825, migrated to Canada and settled in the Gagetown area in the early 19th century.(5) There, he and his wife Jane Eliza Douglas(6) raised their family amidst the verdant countryside. By 1901, Summerhill had blossomed into a vibrant farming community, its residents proudly preserving their linguistic legacy, passing down the Irish tongue through the generations enabled by community-wide transmission. John’s children and grandson John Edward, all born in New Brunswick, were proudly listed in 1901 as native speakers of Irish. In maintaining Irish in the forests and valleys of Gagetown, it had become an integral part of their identity as Canadians:

“It is apparent that the language was being passed on to, at least, the third generation. The language did not cease to exist after the initial immigrant generation.”(7)

Yet, beneath the surface of this seemingly vibrant Gaelic tapestry lay a darker truth. In a deliberate act of erasure, entries declaring Irish as a first language in the 1901 census were crudely overwritten with "English" by census reviewers, obscuring the rich linguistic heritage of the Gagetown Gaels.(8) Every Irish-speaking member of the Armstrong family was overwritten.

A Sudden End

As the early 20th century unfolded, with mounting pressure to assimilate during the World Wars and with no outside recognition, the language quietly faded, its final speakers dwindling into obscurity by mid-century. The communities that once stood testament to these early settlers were uprooted in 1953, as the Canadian Armed Forces claimed the plateau for a new training facility, displacing around 900 residents across 20 towns with little warning. Resident Connie Denby remembered, “Everyone was crying and upset, and we put as much of the personal belongings and furniture in the back of a logging truck with sideboards that we could get.”(10)

The landscape once dotted with thriving farms and bustling towns now lay desolate, its inhabitants scattered far and wide, as a reporter for MacLean’s magazine described in the year after the expropriation: “Dirt roads wind through dark woods past ghost villages… Numerals painted on each empty house, each school, church, barn and privy signify that the army has taken over.”(11) In time, memory of the language’s very existence in the Gagetown area was overwritten. In interiews with descendants, Dr. Peter Toner, census study lead, discovered that many denied their families’ Gaelic origins altogether.(9) With the home communities shattered, John E. Armstrong moved onwards to Ontario, where he died in 1978, marking the end of an era for the Gagetown Gaels and their linguistic heritage.

For citation, please use: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “The Gagetown Gaels.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

-

Placenames indicating the origin of Irish settlers include: Hibernia (Latin for Ireland), Clones (Monaghan), Coote Hill (Cavan), Enniskillen (Fermanagh), and Summerhill (Antrim)

Mac Aonghusa, Proinsias. “Reflections on the Fortunes of the Irish Language in Canada, with some reference to the fate of the language in the United States.” O’Driscoll, Robert and Reynolds, Lorna. The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada. II. 712

Gaunce, Bradford. “Gagetown: a Mini Gaeltacht in New Brunswick?.” 19th Atlantic Studies Conference. University of New Brunswick. Saint John. 5 May 2012. Lecture.

Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” 1.

Four John Armstrongs arrived 1833-1834, all departing from the port of Ballyshannon, Donegal.

Born in the United States of Scottish heritage.

Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” Diss. University of New Brunswick, 2013. 36-37.

This also occurred against Indigenous language and Acadian French, also desired to be seen as “passing away,” and similar erasures against Irish can be found in census results across the Canadian East Coast, Quebec, and Ontario, as well as in Ireland itself. As Gaunce notes, there was a “...seemingly independent or collective effort to under-play the use of the Celtic languages in nineteenth-century Canada.” Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” 47.

“When I checked with some families who had forebears recorded in that census as M[other] T[ongue] Irish, most flatly denied that the Erse Language was ever spoken in their families,” adding that it is under this derogatory term (Erse) that the language is remembered in New Brunswick: “and it is used as the pejorative that it is.” Toner, Peter. “Dialann De hÍde.” Message to Daniel Doyle. 29 Aug 2012. Personal Correspondence.

Webb, Stephen. 2022. Nearly 70 years later, CFB Gagetown expropriation still resonates. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/cfb-gagetown-expropriation-70-years-later-1.6525278

As mentioned in: Ibid. Original source: 1954. “The Private Army We're Giving the Army - Camp Gagetown, New Brunswick” MacLean’s. Sep 15. Toronto.