The Primeval Language of Man (1899)

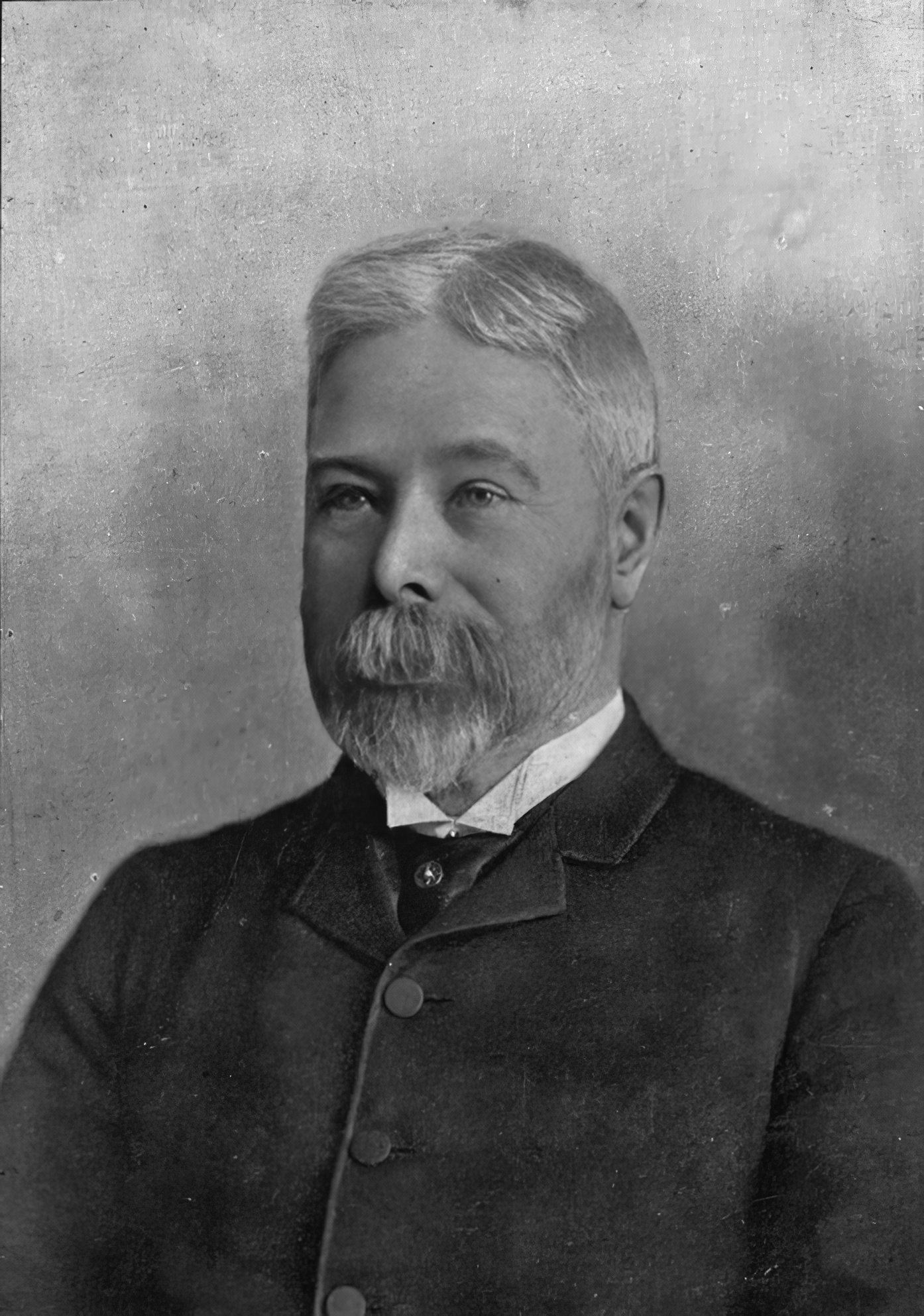

Felix Carbray of Québec City, Québec

In 1899, Québec City’s Tara Hall hosted a lecture by prominent Québec politician Felix Carbray. Against the prevailing political currents of the time, the Irish-speaking Carbray advocated for the revitalization of the Irish language, positioning it among the world's paramount languages. With a fervent call for the revival of Irish in both Ireland and North America, Carbray's passionate stance drew attention to a linguistic heritage that transcended geographical boundaries. The lecture not only captured the imagination of the local audience but also reverberated globally. Reprinted by Conradh na Gaeilge, Carbray’s call for the renaissance of the Irish language spread on both sides of the Atlantic.

The lecture is presented here for consideration, but must be understood within its context. Grounded in the cutting-edge comparative study of Indo-European languages of the time, it is now dated by its use of racial theory and by assuming that Indo-European languages were the source of all world languages. It must be kept in mind that the term “Aryan” was an academic term for the Indo-European language family in 1899, well before its use in Nazi racial ideology. Where Indo-European is used in square brackets below, it may be taken that “Aryan” is used in the original text. Carbray does not appear to have used academics’ hierarchy of languages as evidence of a racial hierarchy, as shown by his financial support of the Métis leader Louis Riel during his defence trial.

“The primeval language of man, of which the Keltic is a dialect, brings us back to the period before the human family had emigrated from the first home wherein they had settled. Men of literary research have found proofs, the most convincing, to show that before the dispersion of the human family there existed a common language, ‘admirable in its raciness, in its vigour, its harmony, and the perfection of its forms.’ The sciences in connection with languages are, in this respect, quite in accord with the tradition of every nation on the globe, and with the teaching of history.

It is certain that there was a primeval speech; that it was once spoken by the people who lived in the high table lands of Armenia and Iran; that it was carried to Europe by the inhabitants who emigrated from the land now ruled by the Shah, that Greek, Latin, Keltic, or Irish, Slavonic or Bulgarian, Lithuanian, Gothic or German, are dialects of that common pre-historic speech. This language, at first one and of the same stock, served as the common medium of inter-communication among the people of the primitive race, as long as they did not extend beyond the limits of their native country… in course of time they spread from Armenia eastward to India and westwards to the extreme limits of Europe, and that they formed one long chain of parent peoples, one in blood and in kin, yet no longer recognising each other as brothers. The name Aryan [Indo-European] has now been accepted by modern philosophers in Europe, as well as in America and in the East. Keltic is [Indo-European]... The Irish race, it is confessed, had been the earliest emigrants from the land of Iran, and had led the van in the great army which came westward to people Europe.

Fuller investigation shows that Irish, with its 16 or 17 primitive letters, had an earlier start westward than either Greek or Latin from the Aryan region - namely, that high table land around Mount Ararat. Immediately after the separation of Sanscrit or Zend from the common stem, the Keltic kept company with the Greek and Latin in a common Greco-Italo-Keltic branch, and there remained the Italo-Keltic, which shot far more to the west, after the Greek had sprouted more to the south, and had attained development...

A thousand years anterior to the days of Homer, and before the Greek was matured in Southern Europe and on the coast of Ionia, the second sprout of the Greco-Italo-Keltic branch was planted in the Italian peninsula and there, like the grain of mustard seed, grew into a large tree, the branches of which ultimately filled the whole earth. The Keltic branch took root for a time in northern Italy. It bore fruit, and, like the oak, scattered its seed to the west in Iberia or Spain, to the north-west in Keltic Gaul, along the banks of the Garonne, the Loire, and the Seine. The best part was wafted to our “noble island,” Inis Alga, where it sprung up and formed the luxuriant tree of Irish Gaelic...

To sum up - from the light which Irish Gaelic throws on the science of linguistic palaiology, the language of Ireland, it must be admitted, is worthy of the attention of students and savants. It opens up, as widely at least as Sanscrit, a field of philological enquiry. In that field its usefulness is admitted to be equal to that of Sanscrit; not only because it is more ready at hand than that ancient eastern tongue, but it once held dominion over the west of Europe, and left, consequently, in the early nomenclature on continental countries its mark on the face of the western world, which Sanscrit did not, and could not have done. Irish Gaelic is for European savants a very ready, practical and truthful vehicle for linguistic research in archaic fields of human speech and of history.

Within the last few years especially the Irish Celts at home and abroad are awakening from their lethargy. A mysterious wave of enthusiasm has seized our race. An ardent longing and desire to revive the old tongue has seized our people everywhere. A most thorough and organised movement has been started by the Gaelic League established in Ireland a few years ago.

I am sure the Irishmen of old Québec will not be behind in the good work. I hope to see at no distant day a branch of the Gaelic League established here. I shall only be too glad to do what lays in my power to help it along. I shall live in hopes that in the near future we shall have in our St. Patrick’s Academy here a Professor of Gaelic, so that the boys may be educated in the grand old tongue of our ancestors - the language of our great monarchs and saints and sages.

May we soon see the day when our ancient language will be again the language of a free and redeemed Ireland.”

About the Author

Felix Carbray, born on December 22, 1835, at Holland Farm near Québec, was a prominent figure in Québec City's Irish community. After working as an accountant for 15 years, he established his own merchant firm and became strongly involved in local Irish organizations, including the St Patrick’s Literary Institute of Québec, contributing to the rise of the community as a potential government lobby group.

In 1881, Carbray entered provincial politics as a Conservative candidate for Quebec West. Carbray won the election in a close race against the city’s former mayor Owen Murphy, which began a long-lasting feud between the two men over who would be the elected voice of the local Irish community. However, Carbray distanced himself from the Conservative party over certain decisions, and the situation worsened after the hanging of Louis Riel in 1885. Carbray, sympathetic to the Métis cause, had supported Riel's trial defense fund and joined in the appeal to the federal government for clemency.

Carbray also strongly advocated for Irish Home Rule, giving impassioned speeches in the legislature, and his resolution on the subject was passed unanimously in 1866.

“The resolution was couched in extremely polite terms to avoid offending the British, but it still prompted heated debate. As a journalist for La Patrie explained, the question of Irish Home Rule in veiled fashion evoked the Riel affair and the disturbing events that his death sentence set off in Québec. The debate revealed the dissension that existed between those who supported ‘the side of the hangmen and Orangemen’ and those who wanted more autonomy relative to the federal government.”(1)

Despite his initial success, Carbray lost his seat to Owen Murphy but returned to represent Québec West in 1892. His ill health led to his withdrawal from politics. Rediscovering his cultural roots, Carbray immersed himself in learning Irish, spending one hour each day studying. He soon became deeply involved in saving the language. Carbray gathered a personal library of Irish manuscripts and books, amassing what the American-Irish Historical Society described as ‘probably the best of its kind in Canada’ at the time.(2) In 1898 he had begun Irish language classes in Québec City, “for the benefit of those anxious to learn the mother tongue.” Carbray, elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy, also beneffited the revival of Irish in Ireland by financially supporting Feiseanna (cultural competitions) in Ulster, Munster, and Galway.

Felix Carbray’s dedication to the Irish language and culture continued until his death in December 1907. With his passing, the power and cohesion of Québec City's Irish community began to dissipate.

Adapted from: Carbray, Felix. 1899. “The Movement in Quebec.” An Claidheamh Soluis. (May 27).

For citation, please use: Carbray, Felix. 1899. “The Primeval Language of Man.” Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

-

Benoit, Jean. 2003. “Carbray, Felix.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. V13. University of Toronto/Université Laval: Toronto.

Irish American Historical Society. 1907. “Hon. Felix Carbray. M.R.I.A., A Member of the Society, Recently Deceased.” The Journal of the American-Irish Historical Society. V7. The Society: Boston.