Focail óm Chroí do Thír mo Ghrá (1885)

Tomás Mac Daibhí de Norradh, composed in New York

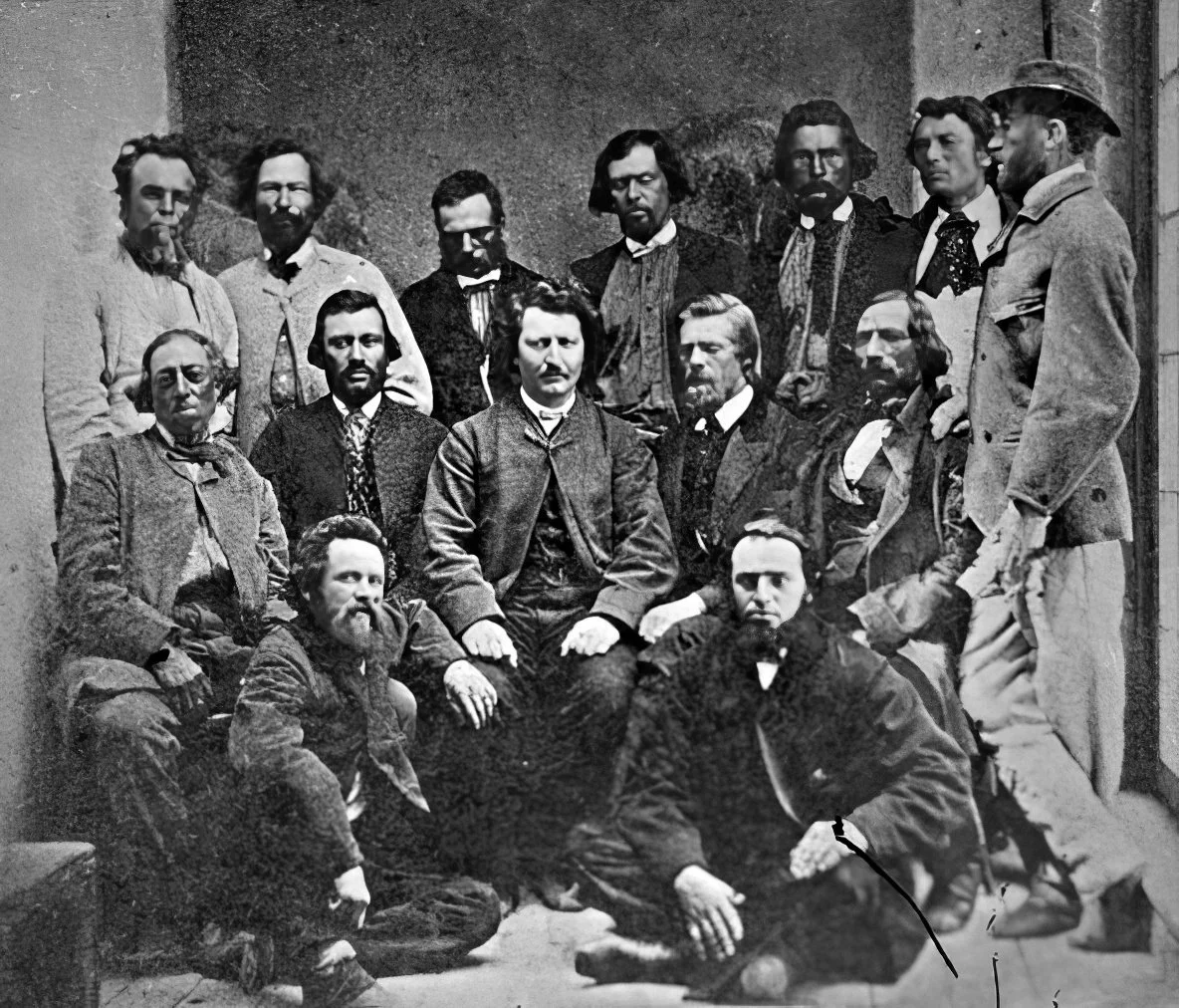

Born in Killarney in 1827, Tomás Dáibhí de Norradh (Thomas David Norris), emigrated to the United States. There, he played a crucial role as a captain in the infantry during the American Civil War in 1863. De Norradh made significant contributions to the preservation and promotion of the Irish language as an executive member of the New York Philo-Celtic Society, and he was a frequent contributor of Irish language materials to publications like the Irish-American and Gaodhal newspapers. His dedication to keeping the Irish language alive in the United States reflected his strong connection to his Irish heritage.

This poem is of special interest as it references the Red River Resistance, an uprising that took place in Manitoba during 1869-1870. The Red River Settlement was home to the Métis people, a unique Indigenous cultural group that evolved from their mixed Indigenous and European ancestry. As Canadian expansion encroached upon their homelands, the Métis feared the erosion of their culture and land rights. In response, they mounted a resistance, led by Louis Riel, demanding a negotiated entry to Canadian Confederation. This resulted in the province of Manitoba.

Brian Ó Baoill interviewed a descendant of the resistance in 1965:

“Duine de na Métis a bhí ann … agus dúirt sé go n-inseodh sé dom scéal Louis Riel agus na Métis. Bhí a athair féin ina fhear óg an tráth sin agus sheas sé le Louis agus lena chomhMhétis i gcoinne na robálaithe ó Uachtar Cheanada. Ba iomaí lá agus oíche a sheas a athair gualainn le gualainn leis na [Bundúchasaigh] nuair a bhí siad araon ag iarraidh a gcearta agus na píosaí beaga talún a bhí gearrtha amach ón bhforaois acu a chosaint ar na creachadóirí ó Toronto…“Bhí saighdiúirí traenáilte agus gach uirlis chogaidh acu siúd, fiú gunnaí móra. Ní raibh go leor armlóin le haghaidh na ngunnaí seilge ag na feirmeoirí. Ach níos measa ná aon rud eile, tháinig lucht an Bhéarla isteach agus ghoid siad uainn an talamh trí chaime.”

“One of the Métis was there… and he said that he would tell me the story of Louis Riel and the Métis. His own father was a young man at that time and stood with Louis and with his fellow Métis against the robbers from Upper Canada. It was many a day and night that his father stood shoulder to shoulder with the Indigenous peoples when they were both trying to protect their rights and the small pieces of land that they had cut out of the forest from the plunderers from Toronto… “Those soldiers were trained and they had every instrument of war, even cannons. There wasn’t enough ammunition for the hunting guns that the farmers had. But worse than anything eilse, the English-speakers came in and they stole the land from us through dishonesty.”(1)

Tomás saw the Métis resistance as a symbol of the global struggle by colonized peoples against the colonial powers. He believed that their fight and success was an omen of the impending downfall of the British Empire. His poem encouraged the Irish, in Ireland and abroad, to stand up for self-determination in the face of oppression.

Is dubhach a bhíonn gach oíche is ló

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Ag smaoineadh ar na bearta crua,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Le chúig céad bliain agus níos mó,

‘Na luí go docht, gan sos, gan só,

Ar Éirinn bhocht, na n-adhbh ceoil.

‘S a clann gan ithe, gan ól;

Ar Éirinn bhocht, na n-adhbh ceoil.

‘S a clann gan ithe, gan ól;

Gloomy is every night and day

Alas! my sorrow!

Thinking on the hard actions,

Alas! my sorrow!

With five hundred years and more,

Oppressing harshly, without rest, without ease,

On poor Ireland, of the musical instruments.

And its children without food, without drink;

On poor Ireland, of the musical instruments.

And its children without food, without drink;

Is súgach sámh do bhí sí am,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Do bhí na Sacsanaigh anonn,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Do bhí Sacsa láidir ‘s Éire fann,

Cé gur thréan ‘s gur chalma iad a clann;

Ach níor aontaíodar le chéile ann,

Is do chaill siad a bhfearainn gan treoir.

Ach níor aontaíodar le chéile ann,

Is do chaill siad a bhfearainn gan treoir.

Peaceful and tranquil it was for a time,

Alas! my sorrow!

The Saxons were across [in England],

Alas! my sorrow!

England was strong and Ireland weak,

Although strong and brave were its children;

But they didn’t unite together then,

And they lost their lands without effort.

But they didn’t unite together then,

And they lost their lands without effort.

Tá fios againn cad do thanú linn,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Chuir Sacsa tiarnaí talúna chughainn,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Do scriosadar is do lomadar sinn,

‘S do chuireadar ruaigeadh orainn thar toinn,

‘S an méid dínn a fágadh thall thar linn,

Níl acu ithe ná ól.

San méid dínn a fágadh thall thar linn,

Níl acu ithe ná ól.

We know what thinned us,

Alas! my sorrow!

The Saxon sent landlords to us,

Alas! my sorrow!

They erased and they denuded us,

And they chased us overseas,

And those of us that were left over there,

They have no food or drink.

And those of us that were left over there,

They have no food or drink.

It is heavy-hearted, gloomy the cause of my tale,

Alas! my sorrow!

That we are scattered through the world,

Alas! my sorrow!

By the English anti-laws and with its rule,

Without having strength to do anything for ourselves,

In meek Ireland with the English devils,

And us spread thinly, separated, without use

When it would be right for our own people to be united as one,

And it would not be long until our rule would be widespread

Is trom-chroíach, dubhach liom cúis mo scéil,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Go bhfuilimíd scaipthe ar fud an tsaoil,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Le haindlí Sacsana is lena réim,

Gan neart againn dada do dhéanadh dúinn féin,

In Éirinn ceannsa le Gallaibh an diabhail,

Is sinn srathnaithe, scartha, gan feidhm

Nuair ba cheart dúinn ár gcine bheith snaímte mar aon,

‘S níorbh fhada gurbh fhairsing ár réim.

If we would unite together now,

Alas! my sorrow!

It is shortly that we would stop the destruction,

Alas! my sorrow!

One single life and one heart,

Desiring the work to practice with force,

And that we would expel the English in the strife

And that we would be, without sorrow, drinking.

Oh! The Irish would be henceforth at home without rent

And they would have merriment and music.

Dá n-aontóimís le chéile anois,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Is gearr go stopfaimis an scrios,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Aon bheocht amháin agus aon chroí,

Le dúil na hoibre chleachtadh le brí,

Is do chuirfimís ruaigeadh ‘r na Gallaibh san stríth

‘S do bheimís gan mhairg ag ól.

Ó! Bheadh Éireannaigh feasta san mbaile gan chíos

Is do bheadh acu imirt is ceol.

There are ten million of our gentle people,

Alas! my sorrow!

In this land who know not their wealth,

Alas! my sorrow!

It is few that would feel the loss of that amount,

That Ireland would be released and the thread broken,

And that the English would be sent home without herds,

And the landlords with them.

But it is evident, my woe, that it is talk without substance,

That is given by most of them (…)

Tá deich milliún dár ndaoine caoin’,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

San dúthaigh seo ‘s gan fios a maoin,

Óchón! mo bhrón!

Is beag do bhraithfidís uatha ‘n mhéid,

Do scaoilfeadh Éire ‘s do bhrisfeadh a téad,

‘S do cuirfeadh na Gallaibh abhaile gan tréad,

‘S na tiarnaí talúna leo.

Ach is follas, mo mhairg, gur bladar gan bia,

An tabharthas ón gcuid acu ‘s mó (…)

(…) There is a daily account coming overseas,

Wonderful! Hurray!

To put happiness of the heart upon us,

If we have love in us

England is attacked on every side,

North and south, east and west,

On sea and on land will be a shower of bullets,

Oh! and that it may fall dead in the tumult.

Oh! Who cares if England is taken away in the name of the devil,

Ireland would be respected forever.

(…) Tá tásc gach lae ag teacht thar linn,

Go breá! hurrá!

Chun áthas cléibh do chur orainn,

Má tá ionainn grá

Tá Sacsana ionsaithe ar gach taobh,

Thuaidh agus theas, thoir agus thiar,

Ar muir is ar talamh beidh stealladh na bpiléar,

Ó! ‘s go dtite sí marbh sa ngleo.

Ó! Is cuma dá mbeire í in ainm an diabhail,

Bheadh Éire faoi ghradam go deo.

Riel is well-founded in Manitoba

Hurray! each day!

And the French of Canada are rising up there,

Hurray! and solace!

India to the east is abiding its time,

And the devil contesting Afghanistan,

Now, let us make a prophecy, if you do not take up blades,

That you will yet be slaves forever,

And that poor, impoverished Ireland without prosperity for its children,

And if possible will be subjugated even more.

Tá Riel i Manatóba teann

Hurrá! gach lá!

Agus Francaigh Cheanada ag éirí ann,

Hurrá! is sólás!

Tá ‘n India thoir ag feitheamh a ham’,

San diabhal á imirt in Afganastáin,

‘Nois, déanaim’ tiorchanadh, mura dtógfaidh sibh lainn,

Go mbeidh sibh ann bhur sclábhaí go deo,

‘S go mbeidh Éire bhocht dealbh ‘s gan rath ar a clainn,

Is más féidir á smachtú níos mó

Across the Great Plains, Indigenous communities were undergoing radical change as the buffalo herds were being exterminated by Europeans, forcing them to fundamentally alter their traditional lifestyles. After his success in Manitoba, First Nations and Métis leaders in Saskatchewan looked to Riel to help protect their own rights and land claims. However, the Canadian Pacific Railway was nearing completion and allowed government troops to swiftly put the “North-West Resistance” down. Riel, a member of the Métis nation, was executed for treason against the settler nation of Canada. Riel would only be formally recognized as the first Premier of the Province of Manitoba by an act of parliament in 2023.

For citation, please use: De Norradh, Tomás. 1885. “Focail óm Chroí do Thír mo Ghrá.” Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

This poem was located only due to the invaluable doctoral thesis: Knight, Matthew Thomas. 2021. “"Our Gaelic Department": The Irish-Language Column in the New York Irish-American, 1857-1896”. Dissertation. Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Adapted from: The Irish American. 1885 (9 May). New York: Lynch, Cole & Co. See the original here.

-

Ó Baoill, Brian. 1965. Idir Huron agus Hudson. Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Tta: Baile Átha Cliath.