Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar

1950-1990: Cultural Reawakening

Tá rian ár dteangacha trasna na mór-roinne seo go hiomlán, ó Thír an Éisc a chur Donnchadh Rua i rannta beoga, agus Alba Nua 'na bhfuil an Ghàidhlig beo fós, go California… stát 'na bhfuil lámhscríbhinn Ghaelach de 686 lgh., a scríobh Tadhg Ó Conaill i mbliain 1827, insan Leabharlann Huntington fós.

- Pádraig Ó Broin (1)

There is a trace of our languages across this entire continent, from Newfoundland which Donnchadh Rua described in lively verses, and Nova Scotia where the Gaelic is still alive, to California… a state in which is the Gaelic manuscript of 686 pages that Tadhg Ó Conaill wrote in 1827, still in the Huntington Library.

Ó hEadhra, Aodán. 1981. The Forgotten Irish. Raidió Teilifís Éireann.

As the language experienced the loss of its final native speakers in Canada, efforts were made to keep the Irish influence alive and to create connections among the dispersed Irish communities in Canada

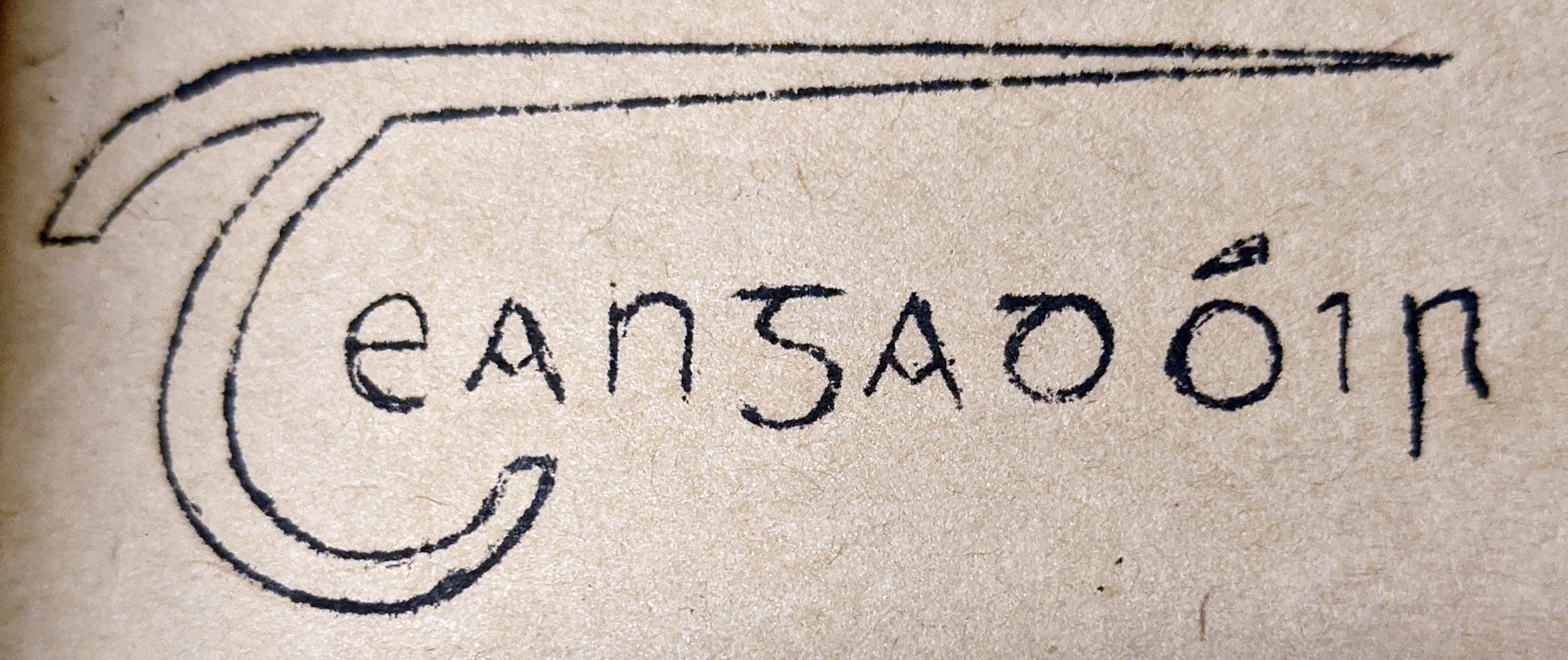

To honour this founding heritage, efforts began in the latter half of the 20th century to document the remaining Irish culture in Canada. The desire to publish Irish materials led in 1939 to the establishment of Cluain Tairbh Press in Toronto. This small publishing house produced both the "Irisleabhar Ceilteach," starting in 1952, and "An Teangadóir," one of the first pan-Celtic magazines in the world, starting in 1955. Folklorists like Joan Finnigan and Edith Fowke recorded the stories and songs of Irish descendants in Ontario and Québec in the 1950s, showing the strong Irish roots of Canadian folk music and the impact of Irish language “sean nós” singing found in traditional Canadian singing styles.(2)

In the 1940s, Don Messer of Tweedside, New Brunswick, began playing his fiddle for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). His immense talent brought traditional Irish-Canadian tunes to national attention, and he would continually use his platform to promote lesser recognized and regional styles, such as Ottawa Valley Step. His melodies danced through radios and televisions, bridging the hearts of countless Canadians. For three decades, Messer's enchanting tunes held audiences captive, and by the 1960s, his show, "Don Messer's Jubilee," had become the second most-watched program in all of Canada, trailing only the iconic "Hockey Night in Canada." Messer was fervent about the roots of Canadian music, proclaiming, "[it’s] not Western or cowboy music. Our tunes have been around for two or three hundred years. They’re folk tunes passed from generation to generation." His legacy illuminated the extraordinary impact of the Irish on traditional Canadian music and dance, ensuring its enduring presence in the Canadian soundscape.

Royal Dionne and Gilles Roy dancing to “Boil the Cabbages Down.” 1950s. From Don Messer’s Jubilee Vol 1. CBC. 1985.

In the aftermath of World War II, increasing prosperity and a wave of new immigration shifted the demographics of historically Irish communities and neighbourhoods, such as Toronto’s Corktown and Cabbagetown. Urbanization also reshaped communities, such as Montréal’s Griffintown and Goose Village communities. The Irish language and culture had thrived for generations in these communities, formed from the slums of Irish Famine refugees near the city’s fever sheds. Residents were displaced and both communities largely demolished in preparation for Expo ‘67. In the 1970s, Québec increasingly enforced the exclusive status of French as the official language. This intensifed the decline of Irish identity in the province as residents from historically Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and English backgrounds departed in large numbers.(3) At the same time, the government of Newfoundland shuttered 250 outport fishing communities, each a bastion of Newfoundland culture. This cultural upheaval was compounded by the devastating collapse of the cod fishery in 1992, resulting in the loss of hundreds more communities in the province.

Loss of Native Speakers

The 1961 census showed the once-vibrant Irish identity was rapidly fading, with less than 10% of Canadians still identifying themselves as ethnically Irish. Despite the efforts of second-language learners to attain and promote the language on a broader scale, those few remaining families that had preserved the language in an unbroken chain were in terminal decline. Children were no longer raised with Irish, and the fact their families had spoken and transmitted it in Canada for generations was hidden out of shame and neglect. John 'Jack' Scallon, the last known native Irish speaker in Québec, passed away in 1953, with his tombstone simply stating “Irish fiddler.” With the passing of each native speaker, any knowledge of the unique Canadian stories, songs, and culture became increasingly limited. Dr. Peter Toner, who grew up around Irish speakers in New Brunswick, recalled: “Many seemed to have survived into the 1960s, but probably most had nobody to talk to.”(4)

Born in 1914, Raymond Creamer of New Brunswick was likely one of the last to be raised bilingually in Irish. With his death in 1988, before any collection work was undertaken, the language in Canada suffered the deep loss. The only pieces of Gaelic-Canadian oral culture preserved in Irish then became those remembered phonetically by English-speakers, with no knowledge of their meaning.

In Newfoundland, a few singers could still phonetically recite songs in Irish into the 1980’s, such as John Joe English, of Branch, St. Mary’s Bay.(5) John Joe was a beloved bastion of Newfoundland culture. His repertoire contained a cherished local ‘Gaelic’ song, Siúil a Ghrá, a faint echo of an earlier time.

Recorded with Anita Best in 1977. Courtesy of the Memorial University of Newfoundland - Digital Archives Initiative

Academic and Cultural Revival

As the language experienced the loss of its final native speakers in Canada, efforts were made to keep the Irish influence alive across the country. In Ireland, an active desire to preserve and promote Gaelic culture had resulted in the foundation of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (Gathering of Musicians of Ireland), an organization with the goal of promoting the national music, culture, and especially the language of Ireland. The organization spread globally, and branches opened across Canada throughout the 1970s, creating connections among the dispersed Irish communities. Canada began to embrace an official policy of multiculturalism, which marked a shift from the once-dominant assimilation expectations, paving the way for diverse cultural identities to flourish.

The academic landscape saw a groundbreaking development with the establishment of the Department of Celtic Studies at the University of St. Michael's College, University of Toronto in 1975. For the first time, higher education in the Irish language became accessible within Canada. UNESCO's support in 1983 further boosted the revival by funding initiatives to teach Celtic languages and promote Celtic cultures worldwide. In 1988, the first comprehensive study of the Irish in Canada titled "The Untold Irish" unveiled the deep-rooted Irish heritage of the country.

In broader advocacy for Irish culture, the existing Gaelic Athletics Association branches across Canada (Toronto, Montréal, Vancouver and Ottawa) joined to form the Canadian Gaelic Athletic Association in 1987, reaffirming their commitment to preserving their cultural roots and Irish heritage.

For citation, please use: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “1950-1990: Cultural Reawakening.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

Any views expressed are those of the author alone, and may not reflect the views of Cumann na Gaeltachta. Any intellectual property rights remain solely with the author.

-

Image Credit: Leabhar na hUidhre. Adapted from: Royal Irish Academy MS 23 E 25 (Leabhar na hUidhre). Meamram Páipéar Ríomhaire.

Pádraig Ó Broin. 1955. “Rian Teangtha na gCeilteach i Meirice.” Teangadóir. 2.9. Cló Chluain Tairbh: Toronto.

Among the Canadian traditional ballads, nearly all of those about sea voyages and shipwrecks, life in the lumbercamps, and tragic accidents in the woods or on the rivers are cast in the typical Irish pattern. It consists of four-line stanzas with seven stresses to each line. The tunes are usually in 6/8 time and the structure is usually ABBA. The rhyme pattern usually is AABB but can vary, especially when it makes use of the characteristic Irish internal rhyme.

Prattis. J.I. 1980. “Ethnic Succession in the Eastern Townships of Quebec.” Anthropologica. New Series 22 (2). Canadian Anthropology Society.

Doyle, Danny. 2015. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. Borealis Press: Ottawa.

This was the experience of Eoin Mhic Comas, a Manx speaker in Kirkland Lake, Ontario: “It was on my mind for a while to start a Gaelic society here but, working three to eleven every day, I could have done nothing to help it along. So, apart from the three young Irishmen - Louis joined the air force, Tommy went to Toronto, John was drowned in the lake - and John Gillis, now blind, I have spoken but little - scarcely a word for over a year… I saw little sense in writing Gaelic that no one was much interested in, so gradually dropped it. Then again, I guess I gradually slowed in my work and the inspiration left me.” Irisleabhar Ceilteach. 1.3. (1953)

Scottish Gaelic was in a similar situation, and in 2001 the last native speaker of Scottish Gaelic in Ontario, Ellic mac Dòmhnaill, passed away. This marked the end of five generations speaking Gaelic in his community of Gleann Garadh. On his deathbed, Ellic said: “All I ask is that someone talk to me in the Gaelic before I go then I’ll be ready.”

It is clear that the words are being recited phonetically, likely with substitions or repetitions added by subsequent English singers. A suggested reading could be “Siúil, siúil, siúil a ghrá /siúil go socair agus siúil go d’reach / siúil go dtí ‘n sagart (a) rúin / is go dtí (dté?) mo mhuirnín sláinte”

All other cited references, numbers, or quotations as from: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall (Doyle, Danny). 2019. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. 2nd Ed. Boralis Press: Ottawa.

Irisleabhar Ceilteach 1.1

The first volume of the pan-Celtic magazine published in 1952 by Pádraig Ó Broin of Toronto, Ontario. It holds correspondence in all three Gaelic languages, submitted by speakers across North America, as well as excertps of prose and poetry.

Formed from the very lively Irish music community in Montréal, and with vocals by Gaeltacht member Chris Mac Raghallaigh, Barde brought prominence to the Gaelic traditions of Québécois and Canadian traditional music.

Irish Independant (16 Mar 1981)

Aloysius (Aly) O’Brien’s family arrived in Freshwater, Newfoundland, in the 1820s. His grandmother, of Kilkenny, was a native Irish speaker. Aly and Dr. John Mannion, brought international attention to Newfoundland’s Irish heritage. (Courtesy of the Memorial University of Newfoundland - Digital Archives Initiative, modified to include next page image)