Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar

1900-1950: An Tost Mór

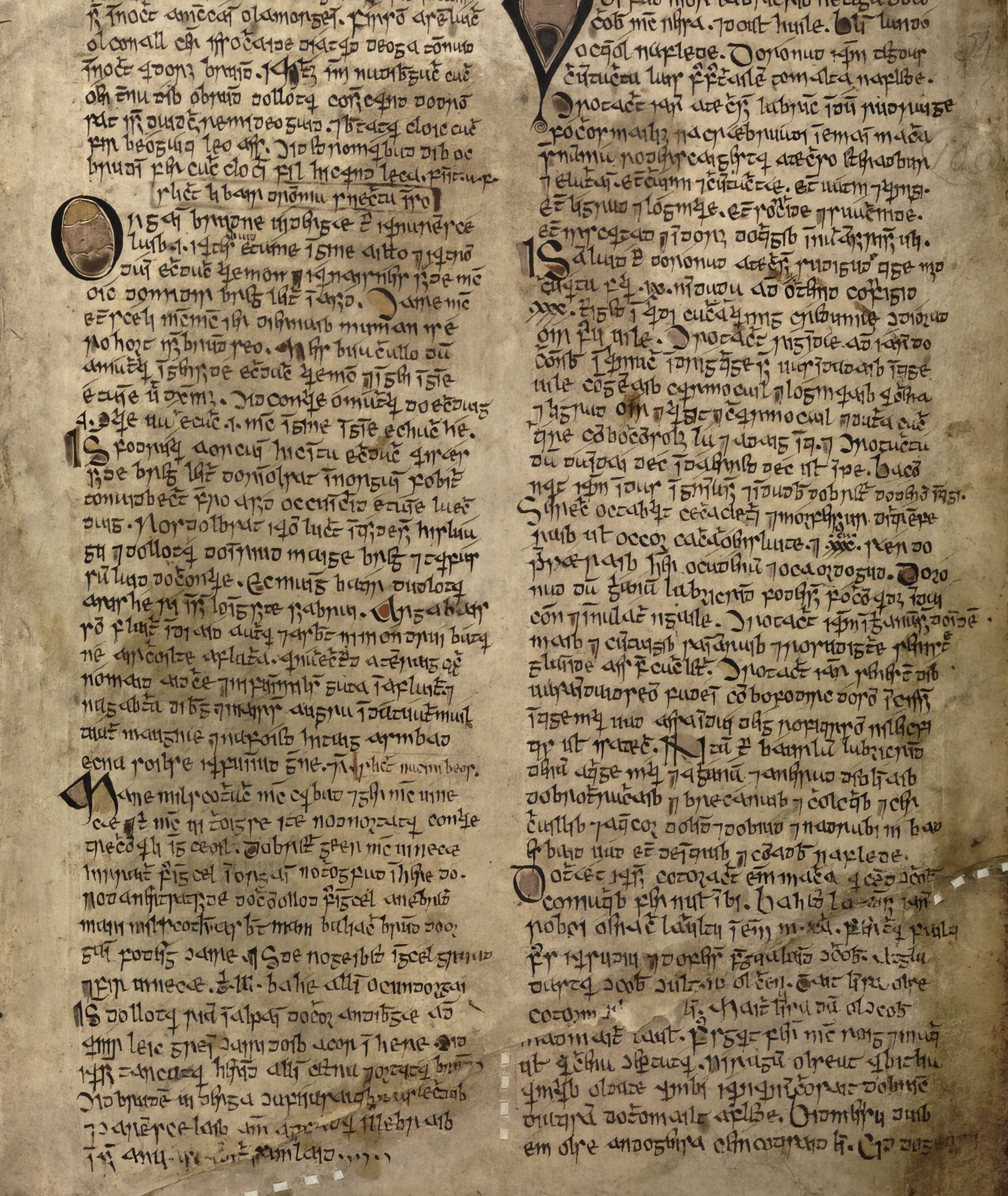

I stand before the Book of Ballymote,

The Book of Leinster, the Leabhar Breac, and last

The oldest, Leabhar na hUidhre – tomes that hold

My people’s history in a thousand ranns:

I cannot read a word.

I do not know the tongue my fathers spoke,

I cannot sing the songs my fathers sang,

I cannot read the books my fathers wrote;

Treasure on treasure in my eager hands:

I cannot read a word.

- Pádraig Ó Broin, “Disinherited” (1)

In ainneoin iarrachtaí caomhnaithe agus úsáid leanúnach i bpobail ar leith, bhí dúshláin shuntasacha os comhair na Gaeilge go luath san 20ú haois, rud ba chúis le laghdú go raibh tionchar aige ar tharchur agus ar fheasacht an phobail araon.

I ndaonáireamh Cheanada 1901, d’fhéadfaí Gaeilge na hÉireann nó na hAlban a liostú mar an chéad teanga a labhraíodh sa bhaile. Léiríonn an daonáireamh seo gur seachadadh an Ghaeilge ar aghaidh ó ghlúin go glúin i measc na nGael i gCeanada. I lonnaíocht amháin a raibh staidéar déanta air, Gagetown, Bronsuic Úr (New Brunswick), bhí 20% den daonra ina gcainteoirí Gaeilge, agus níor rugadh ach mionlach díobh in Éirinn.(2) D’ainneoin an anachain, bhí an teanga tar éis teacht slán ar fhód Cheanada agus tá taifid ann go raibh leanaí á dtógaint le Gaeilge i gCuebec (Québec), in Ontáirio (Ontario) agus i dTalamh an Éisc (Newfoundland). Mar sin féin, bhí go leor leanaí na nGael den ré seo ag fás aníos gan a fhios acu riamh cén teanga a labhair a ngaolta níos sine le chéile, go háirithe i dteaghlaigh a raibh tráma an Ghorta Mhóir orthu.(3) Fiú na daoine a chláraigh iad féin go bródúil mar chainteoirí Ghaeilge, d’fhorscríobh oifigigh rialtais a gcuid iontrálacha chun “English” a rá in ionad “Irish”.(4)

Iarrachtaí Caomhnaithe

De réir mar a lean úsáid na Gaeilge ag dul i laghad, bunaíodh cumainn chun an teanga a chaomhnú i gCeanada. Bunaíodh The Gaelic Revival Association of Ottawa, Cumann Gaelach Ottabha, i 1901. Bunaíodh Ancient Order of the Hibernians in Ontáirio i 1904 agus bhí sé mar aidhm acu oideachas Gaeilge a thabhairt isteach sna scoileanna agus leabhra Gaeilge a chur ar fail sna leabharlanna poiblí.(5) Thug Dubhghlas de hÍde, bunaitheoir Chonradh na Gaeilge in Éirinn, léachtaí poiblí ar athbheochan domhanda na teangan, agus tharraing na léachtaí seo sluaite móra. D’fheastrail 1,200 duine ar léacht amháin díobh i dTorontó in 1906. Bhí craobhacha Chonradh na Gaeilge le feiceáil i gcathracha móra ar fud na mór-roinne, ina measc, Torontó, Ottabha, Montréal, Cathair na Cuebice (Québec), agus Baile Sheáin (St. John’s). Bunaíodh Cumann Muinntearach na n-Gaedheal i Woodstock, Ontáirio, i 1908 chun pobal a chruthú i measc cainteoirí agus scríobhnóirí Mheiriceá Thuaidh.(6) Thosnaigh an Cumann seo ag dáileadh An Bád Beag Glas, iris ar an mbeagán ar domhan ag an am a bhí go hiomlán trí mheán na Gaeilge.(7)

Dúshláin agus Cur i gCoinne

Bhí cur i gcoinne ann in aghaidh na n-iarrachtaí chun an teanga a chaomhnú ó ghnáthshochaí Bhéarla Cheanada. Bhí na nuachtáin ag caitheamh anuas ar Conradh na Gaeilge, agus á lipéadú mar Fhíníní, mar sceimhlitheoirí, nó mar ídéalaithe míthreoracha. Fén gCéad Chogadh Domhanda, bhí cosc ar nuachtáin Éireannacha i gCeanada mar fhoinse ceannairce.(8) Chabhraigh go leor Ceanadach leis an iarracht chogaidh trí dhul isteach i reisimintí Éireannacha, agus d’fhulaing pobail ar fud Cheanada caillteanais mhóra. Le linn an Dara Cogadh Domhanda, chuir Rialtas Cheanada cosc ar Ghaeilge (na hAlban go háirithe). Le brú ó gach taobh, tháinig meath tapa ar tharchur na teangan. Ní de réir faillí amháin a chuaigh an teanga i léig; bhí sé ceilte d’aon ghnó as náire, mar a thug Proinsias Mac Aonghusa faoi deara:

“Could it have happened so gradually that it went unnoticed? This would appear to be most unlikely...Were the children of the original settlers ashamed of the fact that their parents spoke English poorly and used a foreign language among themselves? Did they deliberately hide this ‘shameful’ fact from their children and so on? It is difficult to think of other likely explanations.”(10)

Imeacht agus Oidhreacht

Is beag nár imigh an Ghaeilge ó fheasacht an phobail le linn an 20ú haois. I Leithinis Avalon i dTalamh an Éisc, lean roinnt teaghlach ar aghaidh ag labhairt na Gaeilge tar éis an Chéad Chogadh Domhanda, ach tháinig deireadh leis an gcanúint áitiúil ar leith a bhíodh acu ag pointe neamhchinnte.(11) Bhí an méid sin imeallú déanta ar an dteanga agus neamhaird tugtha uirthi, gur beag suntas a thug Ceanada an Bhéarla nó Ceanada na Fraincise ar a meath. Fé dhaonáireamh 1931, bhí an teanga imithe i léig i gCeanada, agus níor tógadh le Gaeilge ach cásanna ar leith de leanaí. Aithnítear anois na torthaí sóisialta tubaisteacha a bhaineann le cailliúint teangan agus cultúir, cé gur beag taighde atá déanta ar na tionchair laistigh de dhiaspóra domhanda na nGael.(12) I gCeanada, deineadh rún náireach den Ghaeilge, ceilte ar leanaí taobh thiar de dhóirse iata. Ba í seo taithí an Dr. Peter Toner, a d’fhás aníos timpeall ar theaghlaigh Ghaeilge i mBronsuic Úr.

“It was a “secret” language in my time, not spoken outside the home, or when others were in the house… The language was seldom spoken when anyone else was around, but once they left, "jabber, jabber" mixed with gossip about the departed company…”(13)

Le haghaidh lua, bain úsáid as: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “1900-1950: An Tost Mór.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

Is tuairimí an údair amháin iad aon tuairimí a nochtar, agus b’fhéidir nach léiríonn siad tuairimí Chumann na Gaeltachta.

-

Tá teideal an ailt seo ag tagairt do De Fréine, Seán. 1978. The Great Silence. Dublin: Mercier Press.

Image citation: Ottawa University (1901) (Ottawa Gaelic Society). Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Series E/ 936-270 NPC.

199th Battalion, The Duchess of Connaught's Own Irish Canadian Rangers. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/ 1964-114 NPC.

Pádraig Ó Broin. 1936. “Disinherited.” Pádraig Ó Broin (J. Patrick Byrne) Papers. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Toronto. MS Coll 00247). This poem was first published in Writer’s Studio, 1936.

Of this poem, Ó Broin wrote: “The first time I was in the University of Toronto Library stacks I took down from the shelves three huge tomes, facsimilies of Gaelic manuscripts, and leafed through them. At the time I couldn’t read a word of Gaelic and out of that bitterness came this poem.”

As Jonathan Dremblins notes, Gaelic speakers, both Scottish and Irish, were prevalent enough to receive explicit mention in the census instructions. See: Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” Diss. University of New Brunswick, 2013.

Seán Ó Ríordáin, born in Ottawa, Ontario, recounted in 1953: “Ní thuigeann mo thuismitheoirí Gaeilg ar bith. Thuig athair mo mháthar Gaeilg go maith, ach níor mhúin sé Gaeilg ar bith dá chlann. Do léios leabhra Éireannaigh nuair bhíos im pháiste, leabhra scríofa i mBéarla [Sacsan]. Do ba leabhra staire agus filíochta iad a bhí ag m’athair, ach is dócha níor léigh sé féin iad. Chuir siad grá Éireann im chroí, nó, b’fhearr do rá, do mhéadaigh siad grá na hÉireann a bhí ansin ó thús. Bhí bród agus grá Éireann ag mo thuismitheoirí, ag mo mháthair go háithrid, ach ag an am céanna, níor dhéinidís rud ar bith a ghoilleadh ar Shasana. Sin é an cás ag formhór na muintire Éireannaigh a bhfuil fios agam orthu, agus is ait an treo aigne é sin, dar liom.” (Teangadóir. 1953. 1 (1). Cló Chluain Tarbh: Toronto.)

Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” Diss. University of New Brunswick, 2013.

Meeting in St. Thomas, their resolution of August 1904 stated “That we, the members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians of the Province of Ontario are of the opinion that Irish history and the Irish language should be introduced into our Separate Schools, and that books relating thereto should be placed on the shelves of the free libraries of this Province, and recommend that the officers and members of all Divisions of the Order in the Province endeavor to carry this opinion into operation.” McLaughlin, Robert. 2013. Irish Canadian Conflict and the Struggle for Irish Independence, 1912-1925. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

The Cumann was founded “to bring about a closer acquaintance, and to cultivate friendship among the Irish speakers and Irish writers in America… it appeals to all lovers of the Irish tongue to join us and co-operate with us in our efforts on behalf of our native speech...” The society was entirely non-partisan, non-political and non-sectarian. Its foundational documents state that any Irish speaker, man or woman, could become a member, and anyone habitually using English would be stripped of their membership.

A circular subscription, an editor was elected for each issue and it would be sent from one member to the next, with each member receiving it adding to it a short essay, story or poem in Irish. “No member need feel any reluctance about contributing to this, as no other member is allowed to write any corrections or criticisms on the face of the article; but every member is requested to write personally and privately to every contributor and correct any errors in his style or grammar. In fact, the chief purpose of the magazine is to give the members an opportunity to increase their familiarity with and their command of their native language. We hope in this way to educate a group of writers that Erin will be proud to call her children.” As a unique snapshot of the Irish speaking population of Canada at the time, even a single issue of this magazine would yield invaluable insights into the remaining Irish Gaelic culture of Canada at the time. However, due to the nature of the magazine’s format it is unknown and unlikely that any issues still exist.

In 1915, two weekly newspapers publishing material in Irish Gaelic, The Gaelic American and The Irish World, were prohibited in Canada due to seditious materials calling for a free Ireland and the resuscitation of the Irish language and Gaelic culture. Any person found with these papers was liable to a fine of $5,000 or five years’ imprisonment.

Ireland had only gained independence two years before the war, and with little money or military stocks remaining had declared itself officially neutral. The Government of Canada believed this neutrality was actually covert support for Nazi Germany, and extended the ban to Cape Breton Gaelic, amid much backlash from speakers there.

Mac Aonghusa, Proinsias. 1988. “Reflections of the Fortunes of the Irish Language, with Some Reference to the Fate of the Language.” The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada. Ed. Robert O’Driscoll and Ed. Lorna Reynolds. Toronto: Celtic Arts of Canada.

Fáinne an Lae. 1925. Uim 279 (23 Bealtaine). Cló Oifig Mhuintir Chathail: Áth Cliath. “Adeir Donnchadh Ó Cuinn, 89 Cnoc Chartuir, San Seán, Talamh an Éisc, go bhfuil bailte ansin go fóill mar a labhrann na Gaeil atá iontu an Ghaeilge i gcónaí. Nach hé an feall é nach bhféachtar lena bhfuil de Ghaeilgeoirí san Oileán Úr ar fad a chur i gcumann le chéile, le go mbéadh meas acu ar a n-urlabhra dílis féin is go mbuanóidís é.“

“Donnchadh Ó Cuinn, 89 Carter’s Hill, St. John’s, Newfoundland, says that there are houses there still in which the Gaels in them still always speak Irish. Isn’t it a treachery that it isn’t seen by Irish-speakers in North America to be associated with each other, so that they would have esteem for their own loyal speech and that they would preserve it.”

“Linguistic colonisation is as near to complete colonisation as is possible. A cultural blindness descends on its victim, an inability to perceive his original universe and its structures as even his immediate ancestors saw them… The personal and cultural possibilities inherent to the mother tongue are no longer available to the colonised and are replaced by those of the coloniser’s language. The linguistically colonised, whether patriot, a seeker of political freedom, or not, is now imprisoned in the referential universe of the domesticated acculturated colonised. No longer able to self-define in terms of his ancestral tongue, nor even interested in doing so, the colonised can only now do so in terms of the image of himself that he sees mirrored in the coloniser’s tongue. These may not always be phrased in flattering terms but in any case his original power to self-define is now all but lost. A universe has disappeared and another one, a foreign one, has magically taken its place.” Mac Síomóin, Tomás. 2020. The Gael Becomes Irish. Independently Published: Dublin. 32.

Doyle, Danny. 2015. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. Borealis Press: Ottawa.

All other cited references, numbers, or quotations as from: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall (Doyle, Danny). 2019. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. 2nd Ed. Boralis Press: Ottawa.

An Bad Beag Glas

Curtha i gcló i 1909 ag Cumann Muinntearach na n-Gaedheal i Woodstock, Ontáirio. Cuireadh fáilte roimh “Gaeilgeoir ar bith nó mac léinn ar bith atá in ann é féin a chur in iúl go soiléir i nGaeilge scríofa” agus thug siad foláireamh “go bhféadfaí ball ar bith a bhíonn ag úsáid Béarla de ghnáth ina chomhfhreagras a scor den bhallraíocht.” Bhí mná i dteideal ballraíochta ar na coinníollacha céanna le fir.

Ar cheann des na taifeadtaí is luaithe ar bhonn tráchtála de phíopaí Uilleann, ba le John agus Cora Card, as Tamworth, Ontáirio an taifead seo (an ceantar ina bhfuil Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir suite).

An Chéad Dán

Dán a chum Pádraig Ó Broin i 1936, ag cur síos ar a mhian a bheith ina fhile Gaelach agus ar an ndíspreagadh a tugadh dó ar an smaoineamh. Chum sé i dTorontó, Ontáirio é agus é lámhscrite aige sa chló Gaelach.

Spotsolas na nÚdar

Beidh leagan Gaeilge de bheathaisnéisí ag teacht go luath